MES CHERES AMIS FRANCAIS,

SI VOUS N'AVEZ PAS D'ENVIE D'ETRE SUR CE BLOG, IL FAUT SIMPLEMENT ME LE DIRE ET JE PEUX LE CHANGER.

MERCI MILLE FOIS.

IAN

Regular readers of this blog - my mother who visits to look at her grandchildren, their aunt too - will know that the first four pictures of every day are of exactly the same thing, and that under the first photo, I post on agriculture and food.

But not today.

If you're new to this blog you will not know how rarely I do anything different.

That beech tree you see there through the cloud in the above photo - that is the first thing I study every day and every day I photograph it.

I very, very rarely write on this blog.

Instead I practice what I call 'Information Ebru'.

Ebru is a Turkish art form, the process of paper marbling that produces constantly changing interwoven patterns.

"We're not a mosaic, different from one another and fixed in glass," a Turkish anthroplogist said, talking about Turkish society. "Ebru is done on water. It is impossible to have clear lines or distinct borders."

The same is true of our the world, and the way we organise the information to look at it.

So I try to connect some dots, leaving space for the reader to either escape to or write their own story about Earth.

This blog is a destination for those who spend most of their lives 'inside', be it their office, airplanes, their own country or their own local media perspective of Earth.

It's a place to escape to, to go 'outside', perhaps to dream.

It's also a destination for people who want to understand what on Earth is going on, but who don't have the time to do so.

I try to filer the already filtered.

Every information source has is its problems (Noam and others, I know); in the time I have available I can only use the one I trust the most in the world - the Paris-based newspaper, the International Herald Tribune, owned by the New York Times

Their talented editors have already compacted the day's events into 20-odd pages. I think they use something in the region of 1% of all the articles that they have access to and which their editors study every day.

What I then do is to take that 1% and post about 1% of that on this blog. (Some of what I post I agree with, some of it appals me. You too can draw your own conclusions.)

However, what I don't do is follow the traditional main stream media (MSM)information hierarchies (with their distinct pages of news by geographical region, opinion and editorial and their sections on business,culture, sport etc.).

My premise is that (MSM) is parochial and uses information hierarchies, and time lines, which serve as barriers to understanding our world. (This is why MSM is in trouble, which is a shame because the better ones, and the better news agencies, are our eyes and ears and they need to be paid. I hope readers click on to the links I provide to http://www.iht.com/ and explore their website and earn them money.)

I then juxtapose pictures of the very simple life I lead along side the Information Ebru, because to understand the narrative of the 6 billion it helps to follow the narrative of just one of them.

I find it humanizes and gives a framework of reference to a story that is otherwise too vast to get a handle on.

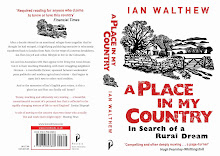

Since the beginning of April, I have been regretfully spending virtually all my days inside, at my computer, working on the PR for the publication of the paperback of my book, A Place in Country, which comes out on 1st, May 2008.

(Why this isn't completely handled by my publisher is another subject for another day, but I have some interesting emails that might explain it and which I may in time post on this blog, if things don't pick up.)

It has not been pleasant: working virtually in 'The Shop', the confinement, the lack of time for my family and friends. It reminds me of a life I once led and will never return to, but all that is better explained in A PLACE IN MY COUNTRY.

Again, If you're new to this blog, you will also know that it is equally rare for me to make a posting of great length.

However, the following edited article (paragraph breaks on this blog normally indicate where I have edited a piece down) from The New York Times Magazine and in the IHT of Saturday, April 12, 2008, seemed to capture so many of the ideas and stories I am interested in.

(It's interesting to note that its web reference is under anthropology, although the IHT ran it as their lead Business section story. Ebru, a Turkish art form, has been used by an anthropologist as a metaphor for society.)

As it also deals with, inter alia, how we communicate - what I have been doing all month - it also seemed a good note on which to announce that www.aplaceintheauvergne.blogspot.com is officially on holiday until the beginning of May.

It's the kids' holidays as of Friday evening, for two weeks (as you can see we spoilt them a bit, they don't have many toys compared with many houses they enter); I have to go to Paris next week for a medical RDV, then return briefly before leaving The Valley and heading to 'The Shop'.

I have also learnt that closely studying, every day, world news, and carefully and slowly comparing other people's experiences with the enormous good fortune of myself and my family, can be a harrowing experience.

I very much want to stop.I won't for at least one full calendar year, but I will enjoy this early spring break.

My main worry about taking this time off is that I will not be here to catch that one day when things change, when the air smells different, when the tint of the budding trees shifts almost imperceptibly into another season's shades.

I don't want to leave, I don't even want to even briefly leave The Valley. As the French would say, we have finally 'put down our suitcases'.

This coming August - if I make it - will be the third anniversary of our time here, and the first time since I was seven when I will have lived, more or less continually, in exactly the same spot for more than three calendar years.

This is my place now. Please explore it while I'm gone.

My story for the year thus far?

If 2007 was the year when the world finally took on board climate change, 2008 will be the year when the world finally takes on board the global food crisis.

Land and water, energy, population, industrialisation, migration, inflation.

I pose the question like this:

6 billion to 9 billion by 2050 = WHAT?

Onwards,

Ian

*****************************

Can the Cellphone Help End Global Poverty?

Chipchase is 38, a rangy native of Britain whose broad forehead and high-slung brows combine to give him the air of someone who is quick to be amazed, which in his line of work is something of an asset. For the last seven years, he has worked for the Finnish cellphone company Nokia as a “human-behavior researcher.” He’s also sometimes referred to as a “user anthropologist.” To an outsider, the job can seem decidedly oblique. His mission, broadly defined, is to peer into the lives of other people, accumulating as much knowledge as possible about human behavior so that he can feed helpful bits of information back to the company — to the squads of designers and technologists and marketing people who may never have set foot in a Vietnamese barbershop but who would appreciate it greatly if that barber someday were to buy a Nokia. What amazes Chipchase is not the standard stuff that amazes big multinational corporations looking to turn an ever-bigger profit. Pretty much wherever he goes, he lugs a big-bodied digital Nikon camera with a couple of soup-can-size lenses so that he can take pictures of things that might be even remotely instructive back in Finland or at any of Nokia’s nine design studios around the world. Almost always, some explanation is necessary. A Mississippi bowling alley, he will say, is a social hub, a place rife with nuggets of information about how people communicate. A photograph of the contents of a woman’s handbag is more than that; it’s a window on her identity, what she considers essential, the weight she is willing to bear. The prostitute ads in the Brazilian phone booth? Those are just names, probably fake names, coupled with real cellphone numbers — lending to Chipchase’s theory that in an increasingly transitory world, the cellphone is becoming the one fixed piece of our identity. Last summer, Chipchase sat through a monsoon-season downpour inside the one-room home of a shoe salesman and his family, who live in the sprawling Dharavi slum of Mumbai. Using an interpreter who spoke Tamil, he quizzed them about the food they ate, the money they had, where they got their water and their power and whom they kept in touch with and why. He was particularly interested in the fact that the family owned a cellphone, purchased several months earlier so that the father, who made the equivalent of $88 a month, could run errands more efficiently for his boss at the shoe shop. The father also occasionally called his wife, ringing her at a pay phone that sat 15 yards from their house. Chipchase noted that not only did the father carry his phone inside a plastic bag to keep it safe in the pummeling seasonal rains but that they also had to hang their belongings on the wall in part because of a lack of floor space and to protect them from the monsoon water and raw sewage that sometimes got tracked inside. He took some 800 photographs of the salesman and his family over about eight hours and later, back at his hotel, dumped them all onto a hard drive for use back inside the corporate mother ship. Maybe the family’s next cellphone, he mused, should have some sort of hook as an accessory so it, like everything else in the home, could be suspended above the floor.

This sort of on-the-ground intelligence-gathering is central to what’s known as human-centered design, a business-world niche that has become especially important to ultracompetitive high-tech companies trying to figure out how to write software, design laptops or build cellphones that people find useful and unintimidating and will thus spend money on. Several companies, including Intel, Motorola and Microsoft, employ trained anthropologists to study potential customers, while Nokia’s researchers, including Chipchase, more often have degrees in design. Rather than sending someone like Chipchase to Vietnam or India as an emissary for the company — loaded with products and pitch lines, as a marketer might be — the idea is to reverse it, to have Chipchase, a patently good listener, act as an emissary for people like the barber or the shoe-shop owner’s wife, enlightening the company through written reports and PowerPoint presentations on how they live and what they’re likely to need from a cellphone, allowing that to inform its design.

The premise of the work is simple — get to know your potential customers as well as possible before you make a product for them. But when those customers live, say, in a mud hut in Zambia or in a tin-roofed hutong dwelling in China, when you are trying — as Nokia and just about every one of its competitors is — to design a cellphone that will sell to essentially the only people left on earth who don’t yet have one, which is to say people who are illiterate, making $4 per day or less and have no easy access to electricity, the challenges are considerable.

From an unseen distance, Chipchase used his phone to pilot me through the unfamiliar chaos, allowing us to have what he calls a “just in time” moment.

There are a growing number of economists who maintain that cellphones can restructure developing countries in a similar way. Cellphones, after all, have an economizing effect. My “just in time” meeting with Chipchase required little in the way of advance planning and was more efficient than the oft-imperfect practice of designating a specific time and a place to rendezvous. He didn’t have to leave his work until he knew I was in the vicinity. Knowing that he wasn’t waiting for me, I didn’t fret about the extra 15 minutes my taxi driver sat blaring his horn in Accra’s unpredictable traffic. And now, on foot, if I moved in the wrong direction, it could be quickly corrected. Using mobile phones, we were able to coordinate incrementally. “Do you see the footbridge?” Chipchase was saying over the phone. “No? O.K., do you see the giant green sign that says ‘Believe in God’? Yes? I’m down to the left of that.”

To someone who has spent years using a mobile phone, these moments are common enough to feel banal, but for people living in a shantytown like Nima — and by extension in similar places across Africa and beyond — the possibilities afforded by a proliferation of cellphones are potentially revolutionary. Today, there are more than 3.3 billion mobile-phone subscriptions worldwide, which means that there are at least three billion people who don’t own cellphones, the bulk of them to be found in Africa and Asia. Even the smallest improvements in efficiency, amplified across those additional three billion people, could reshape the global economy in ways that we are just beginning to understand.

It may sound like corporate jingoism, but this sort of economic promise has also caught the eye of development specialists and business scholars around the world. Robert Jensen, an economics professor at Harvard University, tracked fishermen off the coast of Kerala in southern India, finding that when they invested in cellphones and started using them to call around to prospective buyers before they’d even got their catch to shore, their profits went up by an average of 8 percent while consumer prices in the local marketplace went down by 4 percent. A 2005 London Business School study extrapolated the effect even further, concluding that for every additional 10 mobile phones per 100 people, a country’s G.D.P. rises 0.5 percent. Text messaging, or S.M.S. (short message service), turns out to be a particularly cost-effective way to connect with otherwise unreachable people privately and across great distances. Public health workers in South Africa now send text messages to tuberculosis patients with reminders to take their medication. In Kenya, people can use S.M.S. to ask anonymous questions about culturally taboo subjects like AIDS, breast cancer and sexually transmitted diseases, receiving prompt answers from health experts for no charge.

Some of the mobile phone’s biggest boosters are those who believe that pumping international aid money into poor countries is less effective than encouraging economic growth through commerce, also called “inclusive capitalism.” A cellphone in the hands of an Indian fisherman who uses it to grow his business — which presumably gives him more resources to feed, clothe, educate and safeguard his family — represents a textbook case of bottom-up economic development, a way of empowering individuals by encouraging entrepreneurship as opposed to more traditional top-down approaches in which aid money must filter through a bureaucratic chain before reaching its beneficiaries, who by virtue of the process are rendered passive recipients. For this reason, the cellphone has become a darling of the microfinance movement. After Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel-winning founder of Grameen Bank, began making microloans to women in poor countries so that they could buy revenue-producing assets like cows and goats, he was approached by a Bangladeshi expat living in the U.S. named Iqbal Quadir. Quadir posed a simple question to Yunus — If a woman can invest in a cow, why can’t she invest in a phone? — that led to the 1996 creation of Grameen Phone Ltd. and has since started the careers of more than 250,000 “phone ladies” in Bangladesh, which is considered one of the world’s poorest countries. Women use microcredit to buy specially designed cellphone kits costing about $150, each equipped with a long-lasting battery. They then set up shop as their village phone operator, charging a small commission for people to make and receive calls. The endeavor has not only revolutionized communications in Bangladesh but also has proved to be wildly profitable: Grameen Phone is now Bangladesh’s largest telecom provider, with annual revenues of about $1 billion. Similar village-phone programs have sprung up in Rwanda, Uganda, Cameroon and Indonesia, among other places. “Poor countries are poor because they are wasting their resources,” says Quadir, who is now the director of the Legatum Center for Development and Entrepreneurship at M.I.T. “One resource is time, another is opportunity. Let’s say you can walk over to five people who live in your immediate vicinity, that’s one thing. But if you’re connected to one million people, your possibilities are endless.”

During a 2006 field study in Uganda, Chipchase and his colleagues stumbled upon an innovative use of the shared village phone, a practice called sente. Ugandans are using prepaid airtime as a way of transferring money from place to place, something that’s especially important to those who do not use banks. Someone working in Kampala, for instance, who wishes to send the equivalent of $5 back to his mother in a village will buy a $5 prepaid airtime card, but rather than entering the code into his own phone, he will call the village phone operator (“phone ladies” often run their businesses from small kiosks) and read the code to her. She then uses the airtime for her phone and completes the transaction by giving the man’s mother the money, minus a small commission. “It’s a rather ingenious practice,” Chipchase says, “an example of grass-roots innovation, in which people create new uses for technology based on need.”

It’s also the precursor to a potentially widespread formalized system of mobile banking. Already companies like Wizzit, in South Africa, and GCash, in the Philippines, have started programs that allow customers to use their phones to store cash credits transferred from another phone or purchased through a post office, phone-kiosk operator or other licensed operator. With their phones, they can then make purchases and payments or withdraw cash as needed. Hammond of the World Resources Institute predicts that mobile banking will bring huge numbers of previously excluded people into the formal economy quickly, simply because the latent demand for such services is so great, especially among the rural poor. This bodes well for cellphone companies, he says, since owning a phone will suddenly have more value than sharing a village phone. “If you’re in Hanoi after midnight,” Hammond says, “the streets are absolutely clogged with motorbikes piled with produce. They give their produce to the guy who runs a vegetable stall, and they go home. How do they get paid? They get paid the next time they come to town, which could be a month or two later. You have to hope you can find the stall guy again and that he remembers what he sold. But what if you could get paid the next day on your mobile phone? Would you care what that mobile costs? I don’t think so.”

In February of last year, when Vodafone rolled out its M-Pesa mobile-banking program in Kenya, it aimed to add 200,000 new customers in the first year but got them within a month. One year later, M-Pesa has 1.6 million subscribers, and Vodafone is now set to open mobile-banking enterprises in a number of other countries, including Tanzania and India. “Look, microfinance is great; Yunus deserves his sainthood,” Hammond says. “But after 30 years, there are only 90 million microfinance customers. I’m predicting that mobile-phone banking will add a billion banking customers to the system in five years. That’s how big it is.”

When he is not doing his field work, Jan Chipchase goes to a lot of design conferences, where he gives talks with titles like “Connecting the Unconnected.” He also writes a popular blog called Future Perfect, on which he posts photographs of some of the things that amaze him along with a little bit of explanatory text. “Pushing technologies on society without thinking through their consequences is at least naïve, at worst dangerous . . . and IMHO the people that do it are just boring,” he writes on his blog’s description page. “Future Perfect is a pause for reflection in our planet’s seemingly headlong rush to churn out more, faster, smaller and cheaper.”

We were sitting under a slow-revolving ceiling fan in a small restaurant in Accra, eating bowls of piquant Ghanaian peanut-and-chicken stew. Chipchase told a story about meeting some monk disciples at a temple in Ulan Bator, when he vacationed in Mongolia a few Decembers ago. (Most of Chipchase’s vacation stories, it turns out, take place in less-developed countries, often in forbidding weather and frequently relating back to cellphone use.) Despite their red robes and shaved heads and the fact they were spending their days in a giant monastery at the top of a windy hill where they were meant to be in dialogue with God, some of the 15 monk disciples had cellphones — Nokia cellphones — and most were fancier models than the one Chipchase was carrying. One of the disciples asked to look at Chipchase’s phone. “So he’s got my phone and his phone,” Chipchase told me. “And as we’re talking, he’s switching on the Bluetooth. And he then data-mines my phone for all its content, all my photographs and so on, which is absolutely fine, but it’s kind of a scene where you think, I’m here, I’m so away from everything and yet they’re so technically literate. . . . ”This is when I voiced a careless thought about whether there might be something negative about the lightning spread of technology, whether its convenience was somehow supplanting traditional values or practices. Chipchase raised his eyebrows and laid down his spoon. He sighed, making it clear that responding to me was going to require patience. “People can think, yeah, monks with cellphones, and tsk, tsk, and what is the world coming to?” he said. “But if you wanted to take phones away from anybody in this world who has them, they’d probably say: ‘You’re going to have to fight me for it. Are you going to take my sewer and water away too?’ And maybe you can’t put communication on the same level as running water, but some people would. And I think in some contexts, it’s quite viable as a fundamental right.” He paused a beat to let this sink in, then added, with just a touch of edge, “People once believed that people in other cultures might not benefit from having books either.”

“For the first time, there are more people living in urban centers than in rural settings,” Chipchase explained as we sat in the shade outside the studio. “And in the next years, millions more will move to these places.” At current rates of migration, the United Nations Human Settlements Program has projected that one-quarter of the earth’s population will live in so-called slums by the year 2020. Slums, by sheer virtue of the numbers, are going to start mattering more and more, Chipchase postulated. In the name of preparing Nokia for this shift, he, Jung and Tulusan, along with a small group of others, spent several weeks in various shantytowns — in Mumbai, in Rio, in western China and now here in Ghana. People in the mobile-handset business talk about adding customers not by the millions but by the billions, if only they could get the details right. How do you make a phone that can be repaired by a streetside repairman who may not have access to new parts? How do you build a phone that won’t die a quick death in a monsoon or by falling off the back of a motorbike on a dusty road? Or a phone that picks up distant signals in a rural place, holds a charge off a car battery longer or that can double as a flashlight during power cuts? Influenced by Chipchase’s study on the practice of sharing cellphones inside of families or neighborhoods, Nokia has started producing phones with multiple address books for as many as seven users per phone. To enhance the phone’s usefulness to illiterate customers, the company has designed software that cues users with icons in addition to words. The biggest question remains one of price: Nokia’s entry-level phones run about $45; Vodafone offers models that are closer to $25; and in a move that generated headlines around the world, the Indian manufacturer Spice Limited recently announced plans to sell a $20 “people’s phone.”Even as sales continue to grow, it is yet to be seen whether the mobile phone will play a significant, sustained role in alleviating poverty in the developing world. In Africa, it’s still only a relatively small percentage of the population that owns cellphones. Network towers are not particularly cost-effective in remote areas, where power is supplied by diesel fuel. “I don’t see cellphones as a magic bullet per se, though they’re obviously very helpful,” says Ken Banks, founder of kiwanja.net, a nonprofit entity that provides free text-messaging software and information-technology support to grass-roots enterprises, mostly in Africa. “Many people in the developing world don’t yet have a phone — not because they don’t want one but because there are barriers. And the only way companies are going to sell phones is to understand what those barriers are.” He cites access to reliable electricity as a major barrier, noting that Motorola now provides free solar-powered charging kiosks to female entrepreneurs in Uganda, who use them to sell airtime. The company is also testing wind- and solar-powered base stations in Namibia, which could bring down the cost of connecting remote areas to cellular networks. “Originally mobile-phone companies weren’t interested in power because it’s not their business,” Banks says. “But if a few hundred million people could buy their phones once they had it, they’re suddenly interested in power.”

Jung and Tulusan [Nokia employees that run mobile participatory design studios] said they’d found this everywhere, the phone representing what people are aspiring to. “It’s an easy way to see what’s important to them, what their challenges are,” Jung said. One Liberian refugee wanted to outfit a phone with a land-mine detector so that he could more safely return to his home village. In the Dharavi slum of Mumbai, people sketched phones that could forecast the weather since they had no access to TV or radio. Muslims wanted G.P.S. devices to orient their prayers toward Mecca. Someone else drew a phone shaped like a water bottle, explaining that it could store precious drinking water and also float on the monsoon waters. In Jacarèzinho, a bustling favela in Rio, one designer drew a phone with an air-quality monitor. Several women sketched phones that would monitor cheating boyfriends and husbands. Another designed a “peace button” that would halt gunfire in the neighborhood with a single touch. Interestingly, the recent post-election violence in Kenya provided a remarkable case study for the cellphone as an instrument of both war and peace. After the government imposed a media blackout in late December last year, Kenyans sought news and information via S.M.S. messages on their phones and used them to track down friends and family who’d fled their homes. Many also reported receiving unsolicited text messages to take up arms. The government responded with an admonition, sent, of course, via S.M.S.: “The Ministry of Internal Security urges you to please desist from sending or forwarding any S.M.S. that may cause public unrest. This may lead to your prosecution.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/13/magazine/13anthropology-t.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=sARA+cORBETT&st=nyt&oref=slogin

French troops seize Somali pirates after hostages are freed

Helicopter-borne French troops swooped on Somali pirates Friday after they released 30 hostages from a yacht, capturing 6 of the pirates and recovering sacks of money - apparently ransom paid by the yacht's owners to win the crew's release.

Witnesses said the helicopters fired rockets at the pirates. But French officials, while confirming that troops had fired on a vehicle with pirates on board, said they had not shot at people, had not fired any missiles and had not killed anyone.

The district commissioner of Garaad, where the attack took place, said the helicopters landed and troops jumped out to grab members of a group of 14 pirates who had just come ashore where three pickup trucks with heavy weapons were waiting.

"Local residents came out to the see the helicopters on the ground," Commissioner Abdiaziz Olu-Yusuf Muhammad said by telephone. "The helicopters took off and fired rockets on the vehicles and the residents there, killing five local people."

In Paris, French officials said that the operation was conducted with minimal use of force for fear of causing collateral damage.

They said a Gazelle helicopter with a sniper on board and a Panther helicopter with three commandos on board were involved in the incident. In addition, two missile-armed Gazelle helicopters stood by in support but did not intervene.

They said the only shot fired was by the sniper to disable the engine of a vehicle containing the pirates.

"No shots were fired directly at the pirates," Jean-Louis Georgelin, chief of the armed forces general staff, told a news conference.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/africa/yacht.php

**********************

PARIS

Former French President Jacques Chirac has undergone surgery to have a heart pacemaker implanted, his office said Friday.

http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2008/04/11/news/France-Chirac-Pacemaker.php

DAMASCUS

A bearish man with a boiling corona of steel-gray hair, Khalifa, 44, has a clownish humor that undercuts his large literary ambitions. He smoked, drank and plowed through a table full of appetizers during a late-night interview at Ninar, a Damascus restaurant popular with Syrian artists and intellectuals, his long answers interrupted by bursts of raucous laughter.

THE novel, he said, took him 13 years to write, and draws on his early years growing up in Aleppo. There he watched the conflict between the Islamists and the security forces of Syria's secular Baath Party become steadily more violent, with what he calls a "culture of elimination" developing on both sides.

"The main thing I wanted to get at was the struggle of two fundamentalisms," he said. "I remember that heaviness, that feeling of death dominating the whole city. You were always surrounded by armed men who agreed on only one thing: If you're not with us, you're against us."

Although the novel is centered on a single Aleppo family, it encompasses the broader global story of political Islam over the past three decades. Some real people make appearances, including Abdullah Azzam, a leader of the Afghan jihad against the Soviet Union and a mentor of Osama bin Laden.

But Khalifa insists he has no interest in social realism or didactic fiction. Political ideology infected the work of too many Arab writers in the 1960s and '70s, he said. His own aims are purely aesthetic, and his heroes are William Faulkner and Gabriel García Márquez. He chose to write about "the Events" not to make a political point, but to give artistic life to the increasingly brutal realities of the world he grew up in.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/12/africa/12khalifa.php

********************

NEW DEHLI,

One of the flattering headlines that greeted the release last week of the first Pakistani film to be shown in India in four decades, one stuck in the mind of the director Shoaib Mansoor.

"We didn't know that Pakistan had such good houses," the headline went, Mansoor recalled in an interview in Delhi.

It was a striking reminder of how little people in India know about the way their immediate neighbors across the border live.

For the past 43 years no Pakistan-made film had been distributed commercially to cinemas in India until Mansoor's "Khuda Kay Liye" ("In the Name of God") premiered here April 4 - a fact that has contributed to widespread ignorance in India about modern Pakistan.

This week, Indian filmgoers were offered a rare glimpse of life on the other side, the architecture, the unfamiliar landscape, the homes and the lifestyles. The film provided an unusual opportunity for audiences here to peer into the lives of middle-class Muslims in Pakistan, a country geographically close, but set apart by such entrenched political hostility that very few Indians have ever visited it.

The release of Mansoor's film (which broke all box-office records when it came out in Pakistan last year) was hailed here as a significant moment in the slow-motion Indo-Pakistan peace process.

An official ban was imposed by the Pakistan government on the distribution and broadcast of Indian movies, after the war between the two countries in 1965 (one of three wars fought between the two nations since the region was split by Partition in 1947). No formal reciprocal order was made by India, but initial political hostility to the idea of showing Pakistani films was superseded in later years by commercial considerations. In the second half of the 20th century, the Pakistani film industry (Lollywood) slipped into severe decline and produced nothing meriting distribution in India, (which is well-served by its own film industry).

Despite the ban, pirated, illegal copies of all the Bollywood hits have always been hugely popular in Pakistan. And in 2006, amid improving political ties, the Pakistan government gradually began to relax its approach, allowing a limited number of Indian films to be screened in cinemas legally.

The effect has been a cultural two-way mirror dividing the two countries, with Pakistan able to observe India (or a glitzier Bollywood version of India), but with Indians unable to see beyond its frontiers.

"Indian films never stopped coming to Pakistan, on DVDs," Mansoor said. "So every Pakistani is absolutely clear about the way of life in India, about how everything works in India. But there is nothing coming in the other direction, with the result that India has very clear misconceptions about Pakistan."

His film was edited in Delhi, where he was, he said, "shocked by the ignorance" of Indian colleagues in the cutting room. "They had very surprising ideas about Pakistan. They asked 'Do you have taxis there?' 'Can women drive?' 'Are women allowed to go to university?' They thought Pakistan consisted entirely of fanatics and mullahs.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/asia/letter.php

********************

BERLIN

Berlin police have found a body that is probably that of a missing Russian artist who had been condemned by the Orthodox Church for an exhibit in her homeland. The death was an apparent suicide, police said Friday.

Anna Mikhalchuk, who moved to Berlin in November, has been missing for three weeks. She created a stir in Russia with an 2003 exhibition that the church considered blasphemous, and was tried and acquitted by a Moscow court on charges of inciting religious hatred.

Police said a body found Thursday in a section of the Spree River running through central Berlin is "in all probability" that of Mikhalchuk.

"So far there are no indications that Ms. Mikhalchuk was the victim of a crime," police said in a statement. "She apparently took her own life."

Police are waiting for autopsy results, due early next week, to determine without a doubt that it is the missing 52-year-old.

http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2008/04/11/europe/EU-GEN-Germany-Russia-Missing-Artist.php

LUDWIGSBURG, Germany

Hundreds of thousands of index cards fill the cellar of the former prison. Each card carries a name and often a list of war-crime prosecutions. A librarian leafs through the indexes, looking for names put forward by callers researching family members they may have never known.

For Schrimm, the face of one such bewildered teenage girl is as vivid a memory as that of her Austrian grandfather, Josef Schwammberger - the "most brutal Nazi" he ever put behind bars.

Schwammberger's purges in a Polish ghetto included shooting 40 children in an orphanage and offering a false amnesty to Jews living underground, only to order them stripped and executed.

After paying 500,000 Deutsche marks to an informant, Schrimm traced Schwammberger to Argentina, which extradited him in 1987.

In his initial interviews, Schwammberger appeared to be a gentle, grandfatherly figure. He told Schrimm he had turned to the pope for help in escaping the advancing allied forces.

But over the course of his trial, he emerged as a sadist who had once encouraged his dog to maul a man to death.

During the hearings, Schrimm received a visit from a 17-year-old girl.

"His granddaughter had read it in the newspapers and wanted to know firsthand if it was true," Schrimm recalled. "She was totally shaken.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/europe/germany.php

JERUSALEM

At least five Palestinians were killed by Israeli tank and gun fire in central Gaza on Friday, two of them boys aged 12 and 13, local Palestinian hospital officials said.

An army spokeswoman, speaking on condition of anonymity under army rules, said the soldiers came under heavy mortar and sniper fire and clashed with local gunmen. She said she had no information about youths having been killed, but that if children were in the area of the clashes, they would have been at risk.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/mideast/mideast.php

*****************************

BOOK REVIEW BY NIALL FERGUSON

Terror and Consent

The Wars for the Twenty-First Century By Philip Bobbitt 672 pages.

$35, Alfred A. Knopf; £25, Allen Lane.

"Terror and Consent" is quite simply the most profound book to have been written on the subject of American foreign policy since the attacks of 9/11 - indeed, since the end of the Cold War. It should be read by all three of the remaining candidates to succeed George W. Bush as American president.

Bobbitt's originality lies in his almost unique ability to synthesize three quite different traditions of scholarship. The first is history. The second is law. The third is military strategy.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/arts/IDLEDE12.php

PRISTINA, Kosovo

A human rights group has urged Kosovo authorities to investigate claims in a book by a former U.N. war crimes prosecutor that ethnic Albanian guerrillas killed dozens of Serbs and sold their organs at the end of the war in Kosovo.

New York-based Human Rights Watch said Carla Del Ponte has presented "sufficiently grave evidence" in her newly published book to warrant an investigation into claims guerrillas took Serbs into Albania, killed them and then sold their organs to international traffickers in 1999.

http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2008/04/11/news/Kosovo-Organ-Trafficking.php

BAGHDAD

The soldiers were told that they might be needed in Sadr City for a few days. Instead, they have been here for almost two weeks and are now preparing to stay longer. The Americans' working relationship with the Iraqis is professional but not always clear.

"There is no good liaison right now between the IA and the coalition forces," Bowen said. "It makes things kind of confusing to come up here not knowing exactly what you are getting yourself into tactical-wise. So you come up, figure out what the tactical situation is and try to push through from there."

As the Iraqi and American officers huddled, the Iraqi lieutenant said some of his soldiers had been receiving threatening calls on their cellphones from members of the Madhi Army warning them to leave. The Iraqi lieutenant could not say how the Mahdi Army obtained their phone numbers, but some Iraqi soldiers who participated in the Basra fighting deserted after their families were threatened.

As the discussions continued, one stocky Iraqi soldier stepped forward and announced that he was not afraid of the fighters from Jaysh al-Madhi —or JAM as it is called by American military — regardless of the threats.

"In case I see a bad guy I will not arrest him," the Iraqi soldier said through an American military interpreter. "I will kill him immediately to get revenge for my guys who were lost."

"That is absolutely understandable," Bowen responded. "If they have a weapon and if you ID them as a JAM member, eliminate the threat."

The militias have their own unique way of signaling the presence of the foes. The Americans say the militias have been using trained pigeons to signal the presence of American and Iraqi troops. The Iraqis wanted to know if they could fire on the pigeon keepers as American troops have done during the bitter fighting here.

As long as the Iraqis determined that the flocks of birds were not a coincidence, the Americans advised, the pigeon keepers were fair game.

"Before the IA came up here this entire area was ridiculously dangerous," he said. But alleys remain a problem.

"Typically, they have not cleared it because they don't have enough troops," Bowen said. "They don't feel secure as they move down these alleyways. I think a lot of that is because they might be new. I think a lot of it is them being green. That is what we are trying to overcome by bringing an American presence up here, giving them suggestions, giving them a helpful shove."

Lewis said the performance of the Iraqi troops had improved noticeably during the Sadr City fight, but added that they also had a long way to go.

"They have their experienced guys," he said. "But there are more new guys than experienced guys. The experienced guys are the ones in the higher ranks, the officers and senior enlisted guys. Down at the lower levels, like squad leader, platoon leader or team leader, there are not very many experienced guys to lead them in the right direction. That is where the problem lies right there."

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/africa/11sadrcity.php?page=2

OPINION

FRANKFURT

Now we are moving another step forward, with emerging markets looking further afield to safeguard and expand their own interests. Sovereign wealth funds (SWF) have been scouring the world for lucrative investment opportunities, and not only in the industrial countries.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the bulk of SWF investment is in fact channeled into other emerging markets - Saudi Arabia, for example, has invested heavily in the Turkish telecom sector and China has focused most of its attention on Africa.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/opinion/edheise.php

OPINION

By now we all have a story about a job outsourced beyond our reach in the global economy. My favorite is about the California publisher who hired two reporters in India to cover the Pasadena city government. Really.

There are times as well when the offshoring of jobs takes on a quite literal meaning. When the labor we are talking about is, well, labor.

In the last few months we've had a full nursery of international stories about surrogate mothers. Hundreds of couples are crossing borders in search of lower-cost ways to fill the family business. In turn, there's a new coterie of international workers who are gestating for a living.

Many of the stories about the globalization of baby production begin in India, where the government seems to regard this as, literally, a growth industry. In the little town of Anand, dubbed "The Cradle of the World," 45 women were recently on the books of a local clinic. For the production and delivery of a child, they will earn $5,000 to $7,000, a decade's worth of women's wages in rural India.

But even in America, some women, including Army wives, are supplementing their income by contracting out their wombs. They have become surrogate mothers for wealthy couples from European countries that ban the practice.

It's the commercialism that is troubling. Some things we cannot sell no matter how good "the deal." We cannot, for example, sell ourselves into slavery. We cannot sell our children. But the surrogacy business comes perilously close to both of these. And international surrogacy tips the scales.

So, these borders we are crossing are not just geographic ones. They are ethical ones. Today the global economy sends everyone in search of the cheaper deal as if that were the single common good. But in the biological search, humanity is sacrificed to the economy and the person becomes the product. And, step by step, we come to a stunning place in our ancient creation story. It's called the marketplace.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/opinion/edgoodman.php

***********************

COMMENTARY

Not long ago, a young Ohio woman named Trina Bachtel, who was having health problems while pregnant, tried to get help at a local clinic. Unfortunately, she had previously sought care at the same clinic while uninsured and had a large unpaid balance. The clinic wouldn't see her again unless she paid $100 per visit - which she didn't have.

Eventually, she sought care at a hospital 30 miles away. By then, however, it was too late. Both she and the baby died.

You may think that this was an extreme case, but stories like this are common in America.

Back in 2006, The Wall Street Journal told another such story: that of a young woman named Monique White, who failed to get regular care for lupus because she lacked insurance. Then, one night, "as skin lesions spread over her body and her stomach swelled, she couldn't sleep."

The Journal's report goes on: "Mama, please help me! Please take me to the ER," she howled, according to her mother, Gail Deal. "OK, let's go," Deal recalls saying. "No, I can't," the daughter replied. "I don't have insurance."

She was rushed to the hospital the next day after suffering a seizure - and the hospital spared no expense on her treatment. But it all came too late; she was dead a few months later.

How can such things happen? "I mean, people have access to health care in America," President George W. Bush once declared. "After all, you just go to an emergency room." Not quite.

According to a recent estimate by the Urban Institute, the lack of health insurance leads to 27,000 preventable deaths in America each year.

And if being a progressive means anything, it means believing that we need universal health care, so that terrible stories like those of Monique White, Trina Bachtel and the thousands of other Americans who die each year from lack of insurance become a thing of the past.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/opinion/edkrugman.php

COMMENTARY

They say the 21st century is going to be the Asian Century, but, of course, it's going to be the Bad Memory Century.

Already, you go to dinner parties and the middle-aged high achievers talk more about how bad their memories are than about real estate.

Already, the information acceleration syndrome means that more data is coursing through everybody's brains, but less of it actually sticks.

It's become like a badge of a frenetic, stressful life - to have forgotten what you did last Saturday night, and through all of junior high.

In the era of an aging population, memory is the new sex.

Society is now riven between the memory haves and the memory have-nots. On the one side are these colossal Proustian memory bullies who get 1,800 pages of recollection out of a mere cookie-bite.

They traipse around broadcasting their conspicuous displays of recall as if quoting Auden were the Hummer of conversational one-upmanship. On the other side are those of us suffering the normal effects of time, living in the hippocampically challenged community that is one step away from leaving the stove on all day.

This divide produces moments of social combat. Some vaguely familiar person will come up to you in the supermarket. "Stan, it's so nice to see you!" The smug memory dropper can smell your nominal aphasia and is going to keep first-naming you until you are crushed into submission.

Your response here is critical. You want to open up with an effusive burst of insincere emotional warmth: "Hey!"

You're practically exploding with feigned ecstasy. "Wonderful to see you too! How is everything?" All the while, you are frantically whirring through your memory banks trying to anchor this person in some time and context.

A decent human being would sense your distress and give you some lagniappe of information - a mention of the church picnic you both attended, the parents' association at school, the fact that the two of you were formerly married. But the Proustian bully will give you nothing. "I'm good. And you?" It's like trying to get an arms control concession out of Leonid Brezhnev.

Your only strategy is evasive vagueness, conversational rope-a-dope until you can figure out who this person is.

You start talking in the tone of over-generalized blandness that suggests you have recently emerged from a coma.

Sensing your pain, your enemy pours it on mercilessly. "And how is Mary, and little Steven and Rob?" People who needlessly display their knowledge of your kids' names are the lowest scum of the earth.

http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/04/11/opinion/edbrooks.php

IW: THE CORRECT SUBTITLE OF MY BOOK HAS ALWAYS BEEN IN SEARCH OF A RURAL DREAM. I DIDN'T WANT A SUBTITLE BUT MY PUBLISHERS INSISTED. WE ARRIVED AT 'IN SEARCH OF A RURAL DREAM'.

ON THE HARDBACK THEY PRINTED 'IN SEARCH OF THE RURAL DREAM'.

IN THE PAPERBACK, THEY GOT IT RIGHT THIS TIME ON THE COVER, BUT WRONG ON THE TITLE PAGE (SEE BELOW) AND WRONG IN THEIR SALES CATALOGUE.

No comments:

Post a Comment